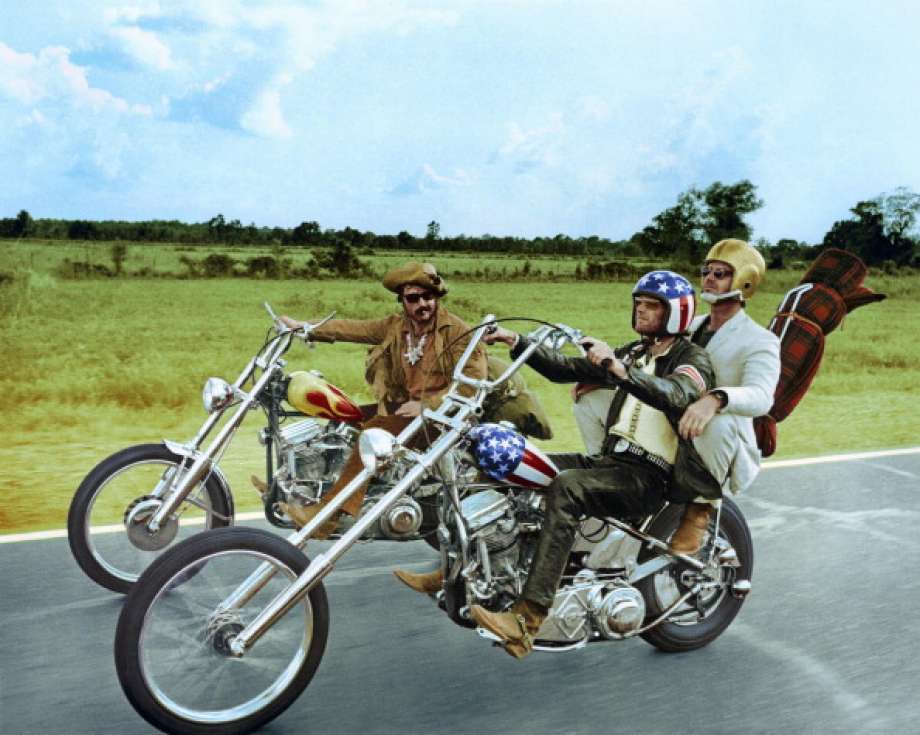

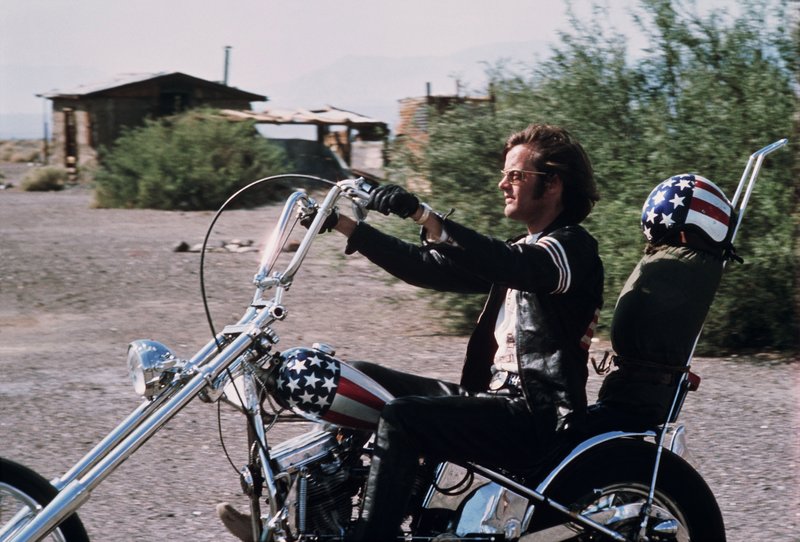

The low-budget rebel odyssey shook the foundations of Hollywood, ushered in a new era and launched a movie star.

This summer marks multiple 50th anniversary spin-offs of 1969 cultural watersheds, from the first moon landing (Neon’s hit documentary “Apollo 11”) and the Manson family murders (Quentin Tarantino’s “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood”) to concert event “Woodstock.”

In the middle of 1969, Dennis Hopper’s “Easy Rider” opened in New York at one theater, ahead of a slow rollout (most of the country did not play the film until September). Now, on the anniversary of the premiere, Fathom Events is bringing it back to over 400 theaters for limited shows on Sunday and next Wednesday.

Decades later, “Easy Rider” is not remembered so much as a great movie–although it did break out Jack Nicholson as a movie star– but more as a shocking commercial success that shook Hollywood’s timbers. The studio reaction to “Easy Rider” changed the industry forever.

Here’s how “Easy Rider” turned into a pivotal Hollywood moment.

Good timing

Both 1967’s “Bonnie and Clyde” and “The Graduate” were cultural game changers that started to break down Hollywood’s working paradigms. In the mid 1960s, the studios were still relying on big-budget musicals (“The Sound of Music”), international spy thrillers (James Bond) and spectacles (“The Bible” and “Hawaii”).

1968 was an outstanding year for studio output: “2001: A Space Odyssey,” “Rosemary’s Baby,” “Bullitt” and “Planet of the Apes” were among the year’s top grossers. But these films were not outsider outlaws that challenged the status quo.

Production takes an average of about eighteen months to adjust to changing tastes, and some early 1969 releases reflected the new spirit of the times, such as X-rated “Midnight Cowboy” which was still rooted enough in conventional drama to win the Best Picture Oscar. That film was “Easy Rider.”

Cannes

“Easy Riders, Raging Bulls,” Peter Biskind’s excellent history of the transitional post-studio era Hollywood world, recounts the film’s full production history. Columbia was already backing co-producer Bert Schneider, who had family ties with the studio, as well as a limited output deal for low-budget projects.

After Roger Corman’s “The Wild Angels” became a sleeper hit, grossing the equivalent of over $100 million on an under (adjusted) $2 million budget, Columbia reluctantly greenlit the “Easy Rider” script about hippie motorcyclists on a cross-country journey starring co-writer Peter Fonda, who before “Angels” was not a top draw, and rookie director Dennis Hopper, who also shared writing credit with novelist Terry Southern.

Hopper, the one-time James Dean costar Hopper (“Rebel Without a Cause,” “Giant”), was struggling with rebellious bad guy supporting roles, including westerns like 1969’s “True Grit.” His most frequent work was guest spots on TV westerns.

Columbia managed to edit the troubled movie into a presentable 94-minute feature. Then to the studio’s surprise, “Easy Rider” was selected for the Competition by the venerable Cannes Film Festival, which had shut down early in 1968 parallel to the French student and worker unrest, and was under siege as out of touch and closed to new ideas.

The film’s entourage walked up the red carpet not dressed to festival code, but they got in and grabbed major press. The jury, presided over by Luchino Visconti as well as Hollywood mainstays Sam Spiegel and Stanley Donen, awarded “Easy Rider” the minor “best first film” prize. Strong reviews out of Cannes gave the film some serious cred.

Columbia’s marketing and release strategy

In the late 60s, the studios gave different kinds of movies different releases. A handful of prestigious A movies for adults opened in top central city movie palaces or other large auditorium single-screen theaters on staggered dates, with higher ticket prices, and exclusive runs before slowly going wider in different stages to less centralized theaters.

When Columbia marketers were faced with a movie needing careful attention, they delivered. They set the film with Cinema 5, then a savvy and trendy Manhattan exhibitor, at their upper east side Beekman Theater, known for playing foreign language films.

“Easy Rider” was an immediate success, and played for a then-record five months. Similarly at its September dates in Chicago the movie showed at the fashionable Esquire Theater, becoming one of only three films to play four months or longer in the previous five years. The other two? “A Man for All Seasons” and “The Lion in Winter.”

Back then theater placement was everything. That was a sea change, and something impossible to imagine without the precedent of “Bonnie and Clyde” (originally slated as a drive-in release by Warner Bros.). A movie about motorcycles and hippies? Lower level exploitation fare.

“Easy Rider” didn’t go into wider release in most places for nearly six months after its its initial New York premiere. Withholding it from general audiences added to interest at a time when moviegoers were aware that for some movies they either needed to travel some distance or wait.

It ended up grossing the equivalent today of around $250 million in the U.S., behind only “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” and “Midnight Cowboy.” Not bad, but sensational compared to its initial budget (around $3 million at 2019 rates).

Impact on the studios

There have been surprise hits since there have been movies. But it’s hard to imagine one since the advent of sound that rattled the foundations of Hollywood more than “Easy Rider.”

Low budget, drug fueled, closer in style to recent European efforts than Hollywood fare, “Easy Rider” befuddled the studio heads, many of whom had been in place for many years and thought they knew what worked.

This movie, generating this level of success, did not compute. Hollywood executives understood pictures like “Hello, Dolly,” “Airport,” “Cactus Flower,” “Patton” — all released within six months of “Easy Rider”– which grossed well on heftier budgets. This came from a different world.

The studios reacted by trying to imitate the formula even if they didn’t understand it. Suddenly all the studios were approving films with young directors, usually with stories related to rebellious, drug-using, sexually-active young people. And most flopped, miserably. The formula was nearly impossible to duplicate.

Schneider’s BBS Productions did show some success during the 70s. Bob Rafelson made “Five Easy Pieces,” with Nicholson in the lead, which scored both critical raves, awards and good grosses. The following year, “The Last Picture Show” did even better. But other films like Columbia’s “Drive, He Said,” “The King of Marvin Gardens,” and “A Safe Place” all flopped. Hopper went on to make five more conventional films, with pro-cop movie “Colors” something of a hit.

Universal, the most conservative, reactionary, and creatively stilted studio, with its feet firmly planted television, had no idea how to respond to “Easy Rider.” Lew Wasserman gave young music label executive Ned Tanen carte blanche to find young directors and give them limited budgets. Among them were Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda. The former went to South America and made “The Last Movie,” a legendary fiasco. The more disciplined Fonda directed “The Hired Hand,” a quiet Western, which also met with near total disinterest. Tanen went on to greenlight George Lucas’s second feature “American Graffiti,” which thanks to producer Francis Ford Coppola, was released with the support it needed and ended up grossing (an adjusted) $600 million.

A star is born

The biggest long-term beneficiary from “Easy Rider”? Jack Nicholson. This journeyman Roger Corman grad and sometime screenwriter was cast in the role of an ACLU lawyer who helps the two lead characters as they get into trouble after Hopper pulled a knife on Rip Torn. Nicholson garnered universal praise for his role, multiple awards, an Oscar nomination (the other for the film was screenplay), and an immediate boost to leading man. After a few uneven years (high points were “Carnal Knowledge” and “Five Easy Pieces”) he finally established himself as a big draw in “The Last Detail” and “Chinatown.”

And…rock soundtracks

A key part of the film’s success was the decision to spend perhaps triple its original budget on current hit songs on the soundtrack. Using otherwise unconnected songs on a score had been a big part of the success with “The Graduate” (mostly Simon and Garfunkel). Here, current songs matched to footage during the editing played so well that initial plans to have Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young compose the score were ditched.

The songs, including top numbers from Jimi Hendrix, Steppenwolf, the Byrds, the Band, and others as much as anything defined the film’s image. The unrelated hit single soundtrack was widely imitated, and is still commonplace. This, along with Nicholson’s career, could be the film’s biggest legacy.